Becoming Undrivable: Florentina Holzinger Crashes in the Same Car

Of course i can't actually drive

In Chaosmosis Guattari uses the example of a patient who is stuck in a rut, going round and round in circles. One day, on the spur of the moment, he decides to take up driving again. As he does so he immediately activates an existentializing refrain that opens up “new fields of virtuality” for him. He renews contact with old friends, drives to familiar spots, and regains his self-confidence. This is what Guattari calls ‘a processual exploitation of event-centred “singularities.”1

A mint green sedan is suspended from a cherry-picker high above the car-park of Werner March’s Olympic Stadium. A cat’s cradle of straps connects it to a burned-out husk of a car below. For tonight’s performance this assemblage is evidently going to play Chekhov’s Gun. It’s going to drop—I mean obviously the car has to drop. But when will she drop it? And how, exactly? And will it go BOOM? In asking such questions we find ourselves assembled once again, in the gloaming at the end of what was supposed to be the Summer of George, awaiting just another virtuosic drop.

Florentina Holzinger’s Schrott-Etüde, a musical “experiment” adjoining Berlin’s Olympic Stadium was billed as an event-centred singularity of sorts. It was also designed, like uh some of the other events to have once occurred in this location, as a virtuosic crowdpleaser (as the RA event description helpfully clarified, ‘According to Frédéric Chopin, “an étude is a musical composition of considerable difficulty, designed to provide practice material for an instrument and its player.” Yet, they are designed to “always please the audience in concert”.) Where it succeeded on the first count (in managing to drag a not-insubstantial portion of the Berlin art-world, fresh off their EasyJet from Marseille, all the way up the U2 for some cultural edification in the last week of their Ferien) it pretty much failed on the latter.

It might well have been meticulous at points (especially the two-wheeled stunt-driving), but the audience remained fairly displeased. Tangible as it was, this buyer’s remorse (which terminated in a pensive “is that really it??” -style pause before the begrudging smatter of applause dribbled out from the crowd after the performance) wasn’t totally deserved. The P.T. Barnum fluff of the event description had after all promised “nudity, use of fire, stunts, and explosion’” as well as “no use of spoken language” and “sound design”. And all of these had been abundantly present . . . for about twenty minutes. There was nudity, there was fire, there were some impressive stunts, and there was an explosion when she finally dropped it (yes, I gasped). Perhaps RA should also have explained that an Étude isn’t a symphony, durationally speaking. Or rather that the temporal grind needed to successfully pull one off – as fiddly as they are – is inversely proportional to the amount of time it takes to actually enjoy listening to one, or ogling in this instance. The FKK paradiddlers, the choreography of the two Olympians trailing their scrapy Schrott capes behind them across the car park, the maniacal stunt-driver’s handbrake donuts, and the undoubtable mass of Health&Safety paperwork it took to pull the thing off, were all evidently pretty labour-intensive undertakings. Yet the resultant Étude remained able to only assemble its various components into one of those incoherent Gastropub charcuterie boards, where everything looks sort of plausible until you actually bite into it and chew (a RiotGrrrl Dinner?); an anti-climatic experience ultimately less satisfying than any of the last few carousels posted on Crisis.Acting’s Instagram (while nevertheless hunting out precisely this same transgressive field of virtuality).

Returning our glasses to the bar to collect the pfand, we pass the mistreated Ken doll visage of Klaus Biesenbach wandering around in a daze. “The car crash is a fertilising rather than a destructive event,” he mumbles.

Still from Stan Douglas’s monodramas.

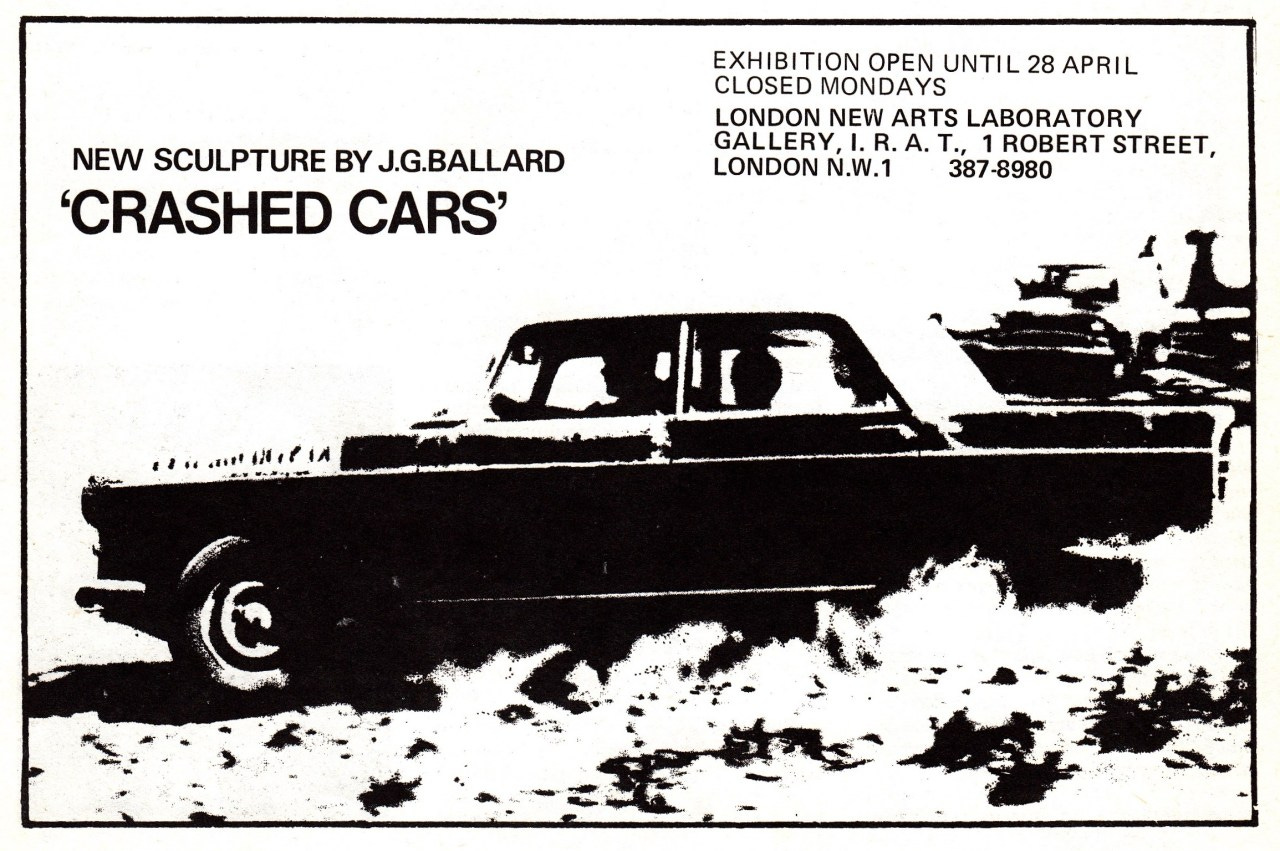

The symbolic scraps Holzinger’s piece ultimately fidgeted with are increasingly familiar. As a friend noted, “in Berlin every 1.5 months we do some repetition compulsion by staging meticulous rituals featuring cars as signifiers of transgression, but with a girlboss twist, perhaps even as a critique of petromasculinity, or a gentle nod to Chris Burden”. This much was already foretold when Julia Ducournau’s Sub-Ballardian mechanophiliac body horror, Titane, went gangbusters a few years ago, and it has since spread throughout the illicit scrap-market that constitutes the Berlin art-world. Take for instance Hannah Rose Stewart and Blackhaine’s MIASMA installation at Trauma Bar and Kino last autumn, or any number of other recent similar petrolhead installations. This dream has a name: becoming undrivable.

A friend recently told me that in Japlish a driver with a license but no real road experience is called a “ペーパードライバ” or a pēpā doraibā: Paper Driver. Becoming undrivable inverts this formula, fabricating metal drivers.

We must become undrivable for the sake of the truly open road. For a road still ungirded by the clutter of signage, for a fresh, still unmarked tarmac and the chaotic freeform manoeuvres it might permit. For the crumpled chassies of John Chamberlain’s sculptures. For John Von Neumann brazenly reading the Times behind the wheel or Jacques Lacan permitting miscellaneous traffic misdemeanours on the grounds that one should throttle one’s desire with norms just because one was in a car.

For a world in which to stall is only to have dreamed too much, where skill comes second, or even third, to the sheer abyssal thrill of one’s body held up shivering into the frigid air on a journey into what thermodynamics permits. Where to career off into a ditch is to seek more than history yet allows.

Every minor transgression now brings us closer to the dream of becoming undrivable, to finally unlearning the cramped bourgeois etiquette of conscientious motoring. For too long we have bad-naturedly motored in muffled and sotto-voce’d consideration of one another, cut up at junctions and clogged up on motorways with the ad-break phantasms of our cars at their most dastardly playing behind our eyelids (our cars shown gliding majestically around hairpin bends in the Mediterranean, on depopulated roads, on a wholly depopulated earth).

Now, becoming undrivable once and for all, we will refuse to indicate or give way in the name of a road without all signals, where the fear of merging is subtended to a more generalized petrification of the motorist, a widespread state of delicious disquiet that such an activity is even possible—where to even motor is to transgress against those who seek to lock us down. It goes it goes it goes.

Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton’s introduction to Félix Guattari’s Three Ecologies, London: Athlone Press, 2000.