‘He is a man with a keen sense of comedy, and a very ready and genial laugh.’ – George Bernard Shaw on Stalin

‘Life has improved, comrades. Life has become more joyous. And when life is joyous, work goes well.’ – Stalin, Speech at the First All-Union Conference of Stakhanovites (1935)

The Joker (TJ): And, as the curtain falls and the packed Apollo disappears from view, as I hear the sibilant thud of simpleton palms slapping against themselves, I find myself returning to the question of The Killing Joke. Returning to the relationship between humour and domination. Or to put it another way, to asking: how can our laughter – as one of the stipulated ‘human monopolies’ alongside language, crying, and the invention of tools, in Pessner’s analysis – reduce our autonomy? And what of their (your) laughter – of its effect on our (my) autonomy?

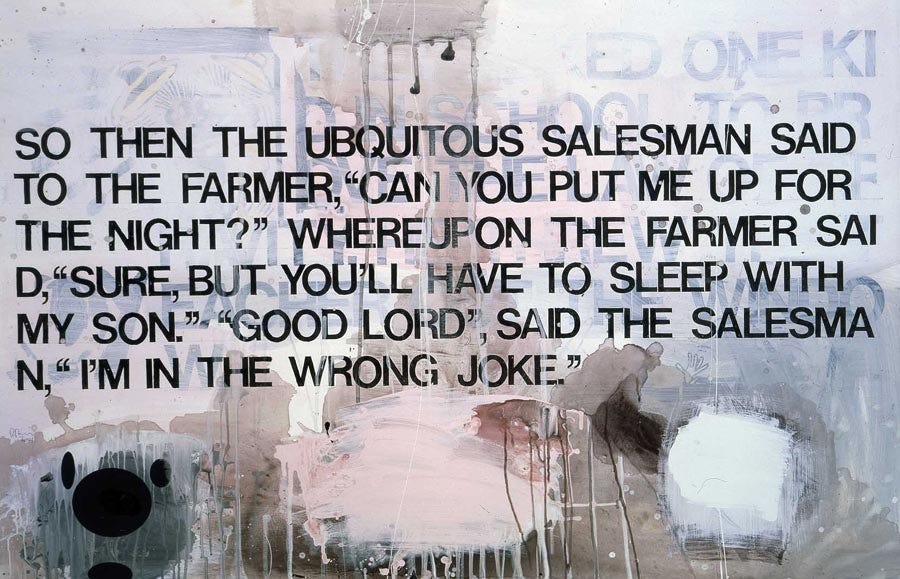

In the Green Room, I consider the peculiar claustrophobia which accompanies a bad taste joke or anecdote (or the receipt of an indelicate meme), when a friend, or senior colleague, or someone you met in the smoking area on a night out, begins to share with us something they’ve evidently previously heard or seen and found funny, but which we’ve already surmised we probably won’t or perhaps as interestingly shouldn’t, and our responses are accordingly heightened, intensified. Or more accurately, our responses to our involuntary responses. This is even more acute, as a professional. Am I frowning? Do I appear censorious, or worse, indulgent? Held captive by the open scenario of the teller’s joke, and the authority the teller has suddenly assumed through their enthusiastic absorption in their joke, and now equally beholden to our response, we begin strategising an exit throughout the joke or anecdote’s delivery – contemplating the means of extricating ourselves before its denouement arrives. As the delivery wears on, our discomfiture increases only further and we can’t help but agonise over the nature of our reaction to the punchline that approaches, as it snowballs through the joke’s repetitions, its onomatopoeia, its myriad silly voices, and absurdities: will we actually be able to prevent ourselves from laughing, or worse, not-laughing?

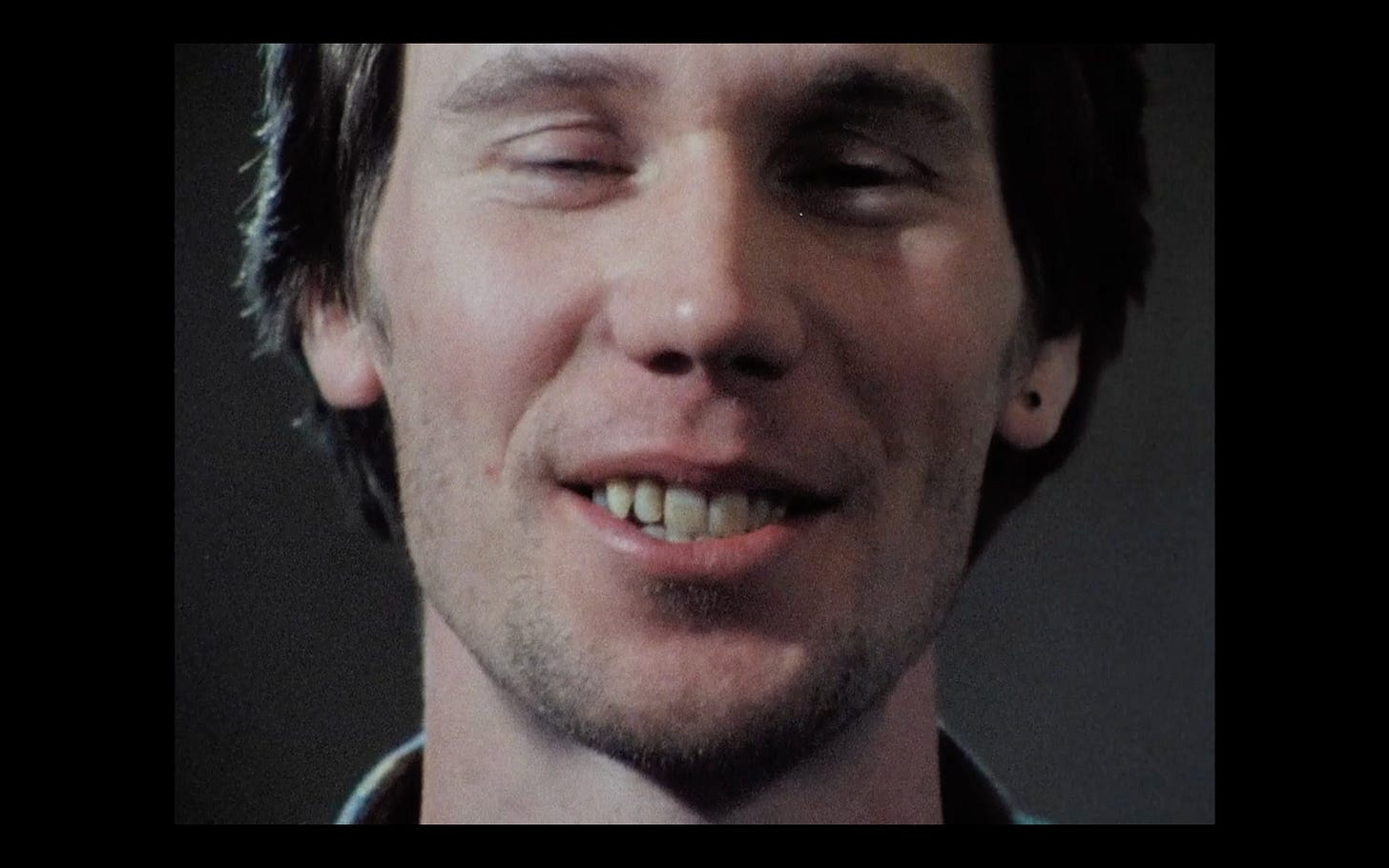

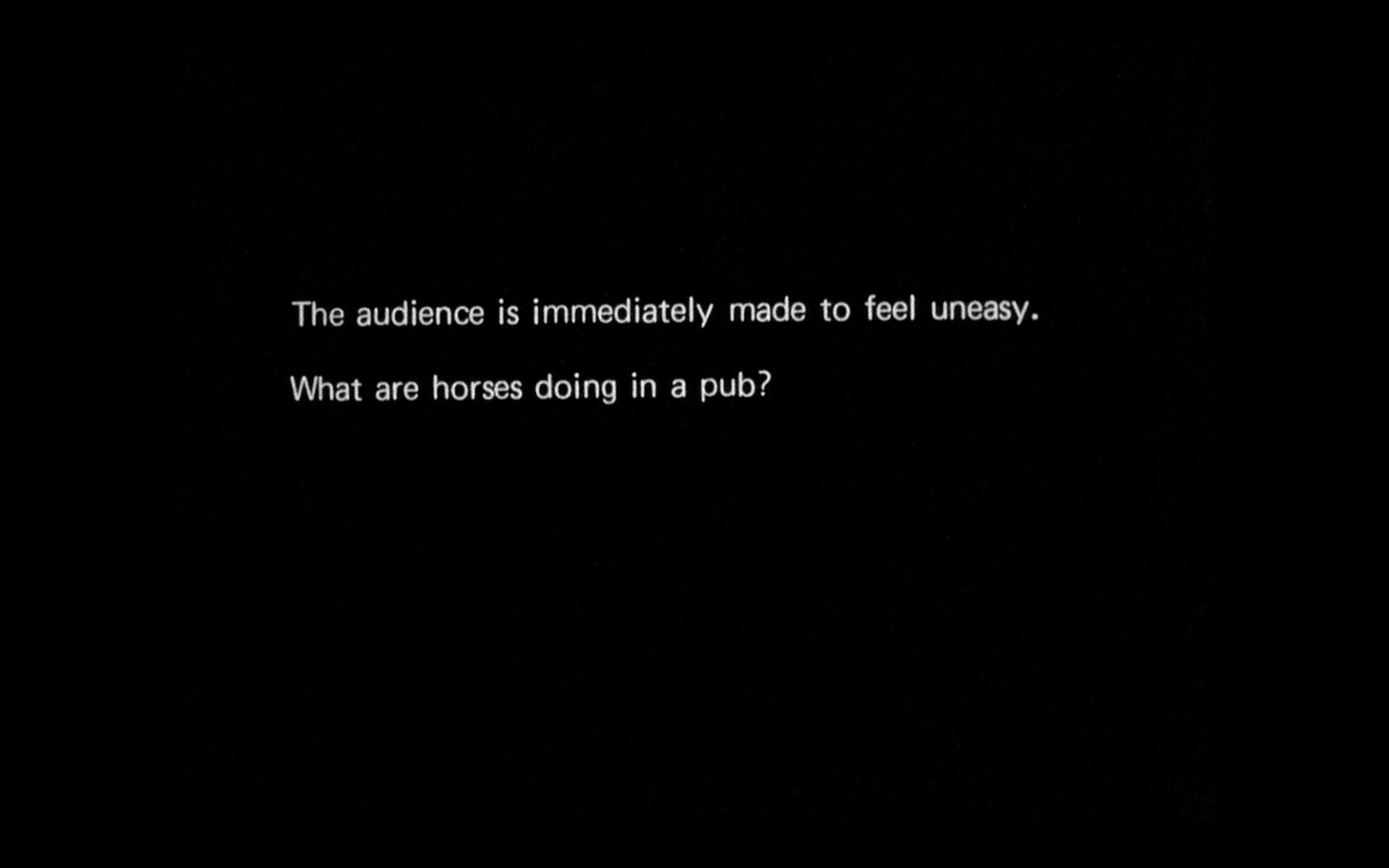

Have you seen John Smith’s Shepherd’s Delight (1980–84)? (The Humourless Regime shakes its head). Well, in it Smith cuts between a static close-up of a working-class joker, his voice and face filled with warmth and geniality, evidently at ease in the position of social control he has momentarily assumed, and solemn white-on-black leader inter-titles psychoanalysing the structure of his joke and the effects it has on its, increasingly neurotic, audience (us) – titles we’re led to associate with the cut-glass RP vowels of the middle-class theorist of the joke whose portentous lecture on the ‘social function of humour’ immediately precedes this sequence. As this farce wears on, one such title reads:

If the audience is amused when the joke ends, it must decide how to react. Unfortunately, saying something like “Actually I didn’t find that funny” can be very embarrassing, since the joke teller will inevitably interpret such a response as a personal criticism. Keeping quiet can be equally problematic. It is more likely that the audience will choose the easiest option and pretend to laugh.

This is a strong theory of comic manipulation, in which we jokers are seen to possess the capacity to reduce our audiences to involuntary nervous eruptions or otherwise paralyse them in knots – a paralysis potentially relieved only by the expulsion of laughter, nervous or otherwise. This paralysis reappears in Norbert Elias’s writing on the defencelessness of the laughing subject:

Laughter, even though it might be hostile and aggressive, indicates to the beholder that the person who laughs is not in a state ready for physical attack. If you are in danger of being physically assaulted, make the attacker laugh (if you can). For the time being, he will be unfit to go on with his assault. Momentarily, laughter paralyses or inhibits man’s faculty to use physical force.

I learned this in the playground: the weaponisation of the good joke (told well) as a kind of somatic domination or possession through and by speech. A potential instrument of self-defence for the puny, the crowded-in, the otherwise spitballed, swirlied, and strong-armed. To return to Pessner’s formulation at the outset of Laughing and Crying: ‘To laugh or cry is in a sense to lose control; when we laugh or cry the objective manipulation of the situation is, for the time being, over.’ This comic vulnerability is there when we speak of actors ‘corpsing’ to describe their lapsing into states of uncontrollable giggles instead of delivering their lines. It’s there also in innumerable ‘killing joke’ scenarios from the Python’s ‘Funniest Joke in the World’ to the (apocryphal) story of Thomas Urquhart, Rabelais’s first translator, who laughed himself to death on having learned that Charles II had reassumed the throne in England. Did you hear that one before?

The Humourless Regime (THR): Quite the scholarly jester, aren’t you? We’ve read of course of such incidences – cardiac arrests and so forth. Take Chrysippus, who died having seen a donkey eat his figs (you really had to be there); or a Mrs. Fitzherbert, who died in October 1781 following three successive days of laughter after having seen a cross-dresser on stage during a performance of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera:

Unfortunately the actor’s whimsical appearance had a fatal effect on Mrs. Fitzherbert; she could not suppress the laugh that seized her on the first view of this enormous representation; and before the second act was over, she was obliged to leave the Theatre. Mrs Fitzherbert, not being able to banish the figure from her memory thrown into hystericks, which continue without intermission till Friday morning, when she expired.

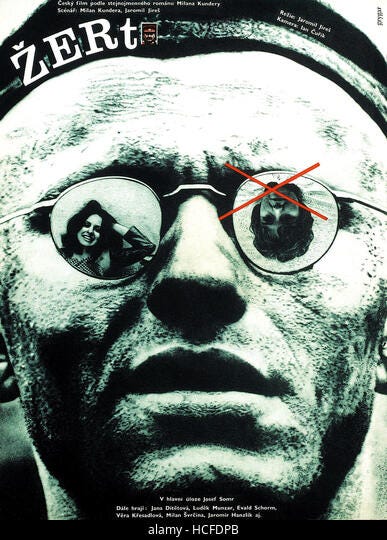

Strange for us, all the same, to hear a comic so animated by the immanent persecution of the joke itself rather than the persecution of the joker. At least since Kundera’s The Joke, and probably before, comics seem to have been on perpetual war-footing against The Humourless Regime: ‘In the future there will be no laughter, except the laugh of triumph over the enemy’, and so on and so forth. It seems every second-rate stand-up or wise guy under the Humourless Regime considers himself a potential Ludvik, a larval Ludvik. Yet what’s often forgotten is how the original Ludvik, Kundera’s fateful joker, is basically tolerated for the first fifth of his novel – his ribaldry and irony, his playfulness, situated just within the boundaries of our acceptability and in any case tempered by his sheer moral and political enthusiasm for The Party. Amidst a group of friends and peers for whom post-45 Czech communism seems only a fait accompli to be navigated without stepping on any toes, and whose enthusiasm therefore carries the whiff of insincerity, Ludvik gains distinction for his prior commitment to the cause as a self-assured student communist. Until, that is, he sends that postcard, derisive of the sanctimony of his crush and her exaltations of the reeducation retreat’s ‘healthy atmosphere’, and dashes off these fateful words in the throes of pining:

Optimism is the opium of the people! A healthy atmosphere stinks of stupidity! Long live Trotsky!

Then it’s curtains for Ludvik. It is for this slight, this – shall we be candid – rather weak gag, that he is ostracised. Expelled from the party and condemned to half a decade in one forced labour camp after another, hauling stones in Sisyphean routines, hatching fruitless plans to escape, nourishing his ressentiment, and pursuing empty affairs. For most of Ludvik’s free-speech fundamentalist fans, that’s where Kundera’s novel finishes: the crime (so-called), the punishment; David, Goliath; their comic discrepancy. Except that’s not actually where the story ends. Nowhere close. The real interest comes when we factor in Ludvik’s eventual, although partial, readmittance into society after he leaves the labour camp. Once again successful and gainfully employed in a laboratory, a beneficiary of the thaw in state repression, his burning ressentiment – the thorn in the flesh – leads him to pursue an affair with the wife of the man who orchestrated his downfall, introducing the novel’s structural ambivalence around its central protagonist.

Surveying our revanchist historical moment and its many other humourless regimes – it’s undeniable that you jokers have been crucial vectors for the dissemination of certain reactionary tendencies over the past two decades. People simply trust you more than they do us. In many cases you helped to build consent for what would (briefly) have been inadmissible had we tried it. You laid the ground. The permissive ‘license to offend’ so integral to the self-image of your profession (stand up!) as an art from Lenny Bruce to Bill Hicks to Dave Chappelle to Russell Brand to sanctioned satirical organs like Charli Hebdo, has hardened over time into a rictus-grin, indifferent to the harm of the offence it registers. Which, furthermore, now largely seeks to offend, and draws its vicious strength from the proof of having registered offence in its audience. Consider ‘Count Dankula’, the portly Scottish edgelord, his face punctured by shrapnel, who instructed his pug to perform a Nazi salute and whose subsequent trial became the free-speech fundamentalist’s favoured instance of persecution for a joke. Or the Swedish king of YouTube, Pewdipie, and his—

TJ: Yes, that’s quite enough, thank you. This all puts me in mind of a joke I once overheard on the Orient Express somewhere in Abkhadazia, a dusty old anekdoty, the kind beloved of the Slovenian School of Lacanian Analysis and its Lackolytes:

Three office workers are being questioned during a purge. It turns out that one of them is always a minute late to work, another a minute early, and the third right on time.

All three are purged from the party:

The first for delinquency,

The second for sycophancy,

The third for bureaucratism.

The structure of such anekdoty is often comfortably uniform, much like the formal straitjacket of our current memes; substitute the names, hang different leaders or Main Characters of the Day onto the joke’s pegs. Take another, which I heard from my lawyer (it was a Russian lawyer):

In connection with the campaign against vulgar naturalism, artistic excess, and cacophony in music, the party committee of a public zoo announced several expulsions:

the rhino, for vulgar naturalism,

the giraffe, for artistic excess,

and the zebra, for cacophony

We may call your regimes humourless, and yet it’s true that your ‘strong men’ continue to outflank us. From Silvio to Johnson, those who have been shown to not take themselves too seriously seem to inspire trust where the Sensibles, their more solemn and serious and studious colleagues, either don’t or can’t. As Aaron Schuster suggests, the liberal hope that the grave realities of political office would sober up a Johnson or Grillo ran aground on their desire to ‘turn the office into a vehicle of perverse enjoyment’. Consider the versatility of Trump’s insistence on nickname rather than the antiquated formal address of high office, so integral to the chummy respectability politics of Clintonite neoliberals – from ‘Crooked Hillary’ to ‘Sleepy Joe’ to ‘Pocahontas’, Trump’s perennial nicknaming, his favoured instrument of derision and deflection, resembles the billingsgate that Bakhtin drew out from Rabelais’ Gargantua.

The Lacanian insight that ‘every discourse is a discourse of enjoyment’ is often deployed to suggest that there can be no meta-discourse, that the neo-Aristotelean dream of a logic outside or beyond language is a fantasy, and therefore, transitively, that there can be no outside to enjoyment. That there is then no getting beyond the joke, for as long as we speak, we produce jouissance (‘language is a factory of enjoyment’, yet a factory which the workers never leave, where no days are lost to strike, where presumably their bathroom trips are also timed). Freud had sought to regulate the libidinal economy and temper the ‘errant surplus’ (Tomsic) he saw represented by ‘excesses’ such as hysterical laughter, thigh-slapping, and block capital fusillades of HAHAHA and LMAOOOO, into a quantifiable measure of ‘normalized enjoyment’. However, for Lacan there can be no such equilibria, or golden mean, to which the psyche can aspire, for ‘enjoyment consists in the positivatization of a lack’. And yet, had Lacan looked out into the Apollo earlier this evening, at these rows on rows of Salaried Masses laughing only on my command (and stopping when instructed), I think he might have reconsidered the status of ‘normalized enjoyment’ . . .

THR: In the Soviet era most of the persecution of jokers happened, when it did, according to a time delay, as a joke formerly deemed innocuous would retroactively come to be seen as a transgression or overstepping of the line. Jokes were prosecuted under Article 58-10 of the Criminal Code, which prosecuted ‘anti-Soviet agitation’. After 1935 anekdoty became regarded as evidence of anti-Soviet agitation. All quotation of jokes (irrespective of context), was then forbidden. A critical joke (if good enough) was figured like a virus in need of immediate quarantining – its proliferation could potentially corrupt and spread havoc.

Jonathan Waterlow has suggested that while, under high Stalinism, the officially sanctioned humour of the Humourless Regime was derisive, and mocking, ordinary humour (contrary to the Kunderian model of resistance) was in fact self-reflexive. Like Mussolini,1 Stalin and his retinue’s humour, such as it was, was largely scornful, mocking, derisory and other-directed; nicknames, impressions, threatening double-entendres. His ludic side was largely that of Nelson the Bully from the Simpsons – scrawling ‘Ha! Ha!’ in red crayon to mark his disapproval in the margins of apparently objectionable documents. A ‘draft collection of the Wit and Wisdom of I.V. Stalin, which remains in his personal archive, is tellingly composed of scorn, sarcasm and other derisive attacks on his enemies’. Soviet stenographers added (canned) instructions for ‘(laughter)’ into transcripts of his published speeches; the Stalinist equivalent of the Friends’ interpassive laughter track. In 1930, at the outset of the Stalinist purges, the regime even convened a special Commission for the Study of Satirical Genres in Art and Literature, headed by A.V. Lunahcharskii. The commission’s main presupposition was that humour constituted a ‘weapon of class struggle’. Such then, for soviet humour from above.

Popular humour below Stalin meanwhile played with an established grammar of tropes belonging to the Humourless Regime, and it is likely that ‘unofficial’ jokes also circulated among members of the regime. Soviet humour from below was about mediating, and thus gaining some control over, the disturbing power of a rapidly changing and disorientating social condition through laughter, via ‘a Schadenfreude directed at oneself’, which Waterlow contrasts with the form of ‘distraction’ that ‘reconciliatory’ humour played in the German Reich. It was, then, an especially desperate form of the Gallows Humour that Freud examined in his famous 1927 essay. In ‘On Humour’, an addendum to his earlier book on Der Witz, Freud turned to the ‘more primary ad important situation of humour’: self-deprecation:

When, to take the crudest example, a criminal who was being led out to the gallows on a Monday remarked: “Well, the week’s beginning nicely,” he was producing the humour himself; the humorous process is completed in his own person and obviously affords him a certain sense of satisfaction. I, the non-participating listener, am affected as it were at long-range by this humorous production of the criminal…

So in a social condition where all were potentially criminals-in-waiting, as David Brandenberger writes, ‘Humor during these years generally functioned as an escape valve of sorts that allowed people to vent their frustrations without committing themselves to anything more than a passing expression of dissatisfaction with the status.’ Against the collectivist counter-narrative, the communal ‘second life’ of Bakhtin’s carnival then, the circulation of anekdoty instead comprised a personal effort to ameliorate suffering in an era of institutionalised sociopathy. To grasp this we should fathom the flippancy of the joke, its slipperiness with respect to the question of commitment, in the ability of so many to tell anti-regime jokes one minute and acquiesce with its needs for informants the next. And doesn’t this just show the crucial distinction between the humour of the state and that of society? Sespite certain points of convergence, ordinary people’s humour was reflexive, whereas the regime’s humour was not. As one joke ran: ‘“How’re you doing?’’ ‘‘Like Lenin – unfed and unburied’’. & Another (& another & another):

Two Soviets are talking:

- What do you think was Adam and Eve’s nationality?

-Soviet, no doubt. They had nothing to wear, only a single apple to eat, and thought they were living in paradise.

The laughter of the fascists was also crude, mocking, and deaf to irony – ‘Mussolini is not a man of humour, nor is he a French-style homme d’esprit. Normally, if anyone allows himself to make a joke in his company, an icy glare will freeze the very words in his mouth. His view of life is highly dramatic and tending towards tragedy; he loves contrasts of light and strong emotions.’